Can you play football with a torn ACL? No, it is not recommended to play football with a torn ACL due to the significant risk of further injury, long-term knee instability, and the potential for career-ending damage. While some individuals may attempt to push through the pain, this approach is highly ill-advised.

A torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a serious knee injury that significantly impacts an athlete’s ability to perform in high-impact sports like football. The ACL is a crucial ligament that provides stability to the knee joint, particularly during rotational movements and sudden stops. When this ligament is torn, the knee becomes unstable, making it vulnerable to further damage.

This in-depth guide will explore the realities of playing football with a torn ACL, the associated risks, the recovery process, and the crucial steps involved in returning to the sport safely. We will delve into the specifics of ACL injury in football, ACL tears in athletes, and what it means to have an ACL rupture.

Image Source: uploads.prod01.sydney.platformos.com

Fathoming the ACL Injury in Football

The ACL is one of the four main ligaments in the knee. It runs diagonally in the middle of the knee and controls rotational movements and forward slipping of the tibia (shin bone). In football, the ACL is particularly susceptible to injury due to the sport’s dynamic nature, which involves:

- Sudden Stops and Starts: Players frequently change direction rapidly, putting immense stress on the knee.

- Pivoting and Cutting: Twisting the knee while the foot is planted is a common mechanism for ACL tears.

- Jumping and Landing: Improper landing after a jump can cause the knee to buckle.

- Direct Impact: A blow to the side of the knee, especially when the foot is planted, can also lead to an ACL tear.

When an ACL is torn, a person often hears or feels a “pop” in the knee, followed by immediate pain and swelling. The knee may feel unstable, giving way during movement.

Common Scenarios Leading to ACL Tears in Athletes

Several common scenarios in football can lead to an ACL tear:

- Non-Contact Pivoting: This is the most frequent cause. A player might be running, pivot quickly to evade a tackle, and the ACL tears as the tibia rotates internally while the femur stays put.

- Hyperextension: If the knee is forced backward beyond its normal range of motion, the ACL can be stretched or torn.

- Landing Awkwardly: Jumping for a ball or making a tackle and landing with the knee bent awkwardly can strain the ACL.

- Direct Blows: While less common for isolated ACL tears, a direct hit to the knee, especially from the front, can contribute to the injury.

Playing Sports With Torn ACL: The Grave Dangers

Attempting to play football with a torn ACL is a high-risk endeavor. The torn ligament cannot adequately stabilize the knee, meaning that any cutting, pivoting, or sudden deceleration can cause the tibia to shift excessively within the knee joint. This excessive movement can lead to a cascade of secondary injuries:

- Meniscus Tears: The menisci are C-shaped cartilage pads that act as shock absorbers between the thigh bone (femur) and shin bone (tibia). With an unstable knee, the femur can grind against the tibia, tearing the menisci. Meniscus tears can cause pain, locking, and further instability.

- Cartilage Damage: The smooth cartilage that covers the ends of the bones in the knee joint can also be damaged. This is known as articular cartilage damage. Once cartilage is damaged, it has a very limited ability to heal, and it can lead to osteoarthritis later in life.

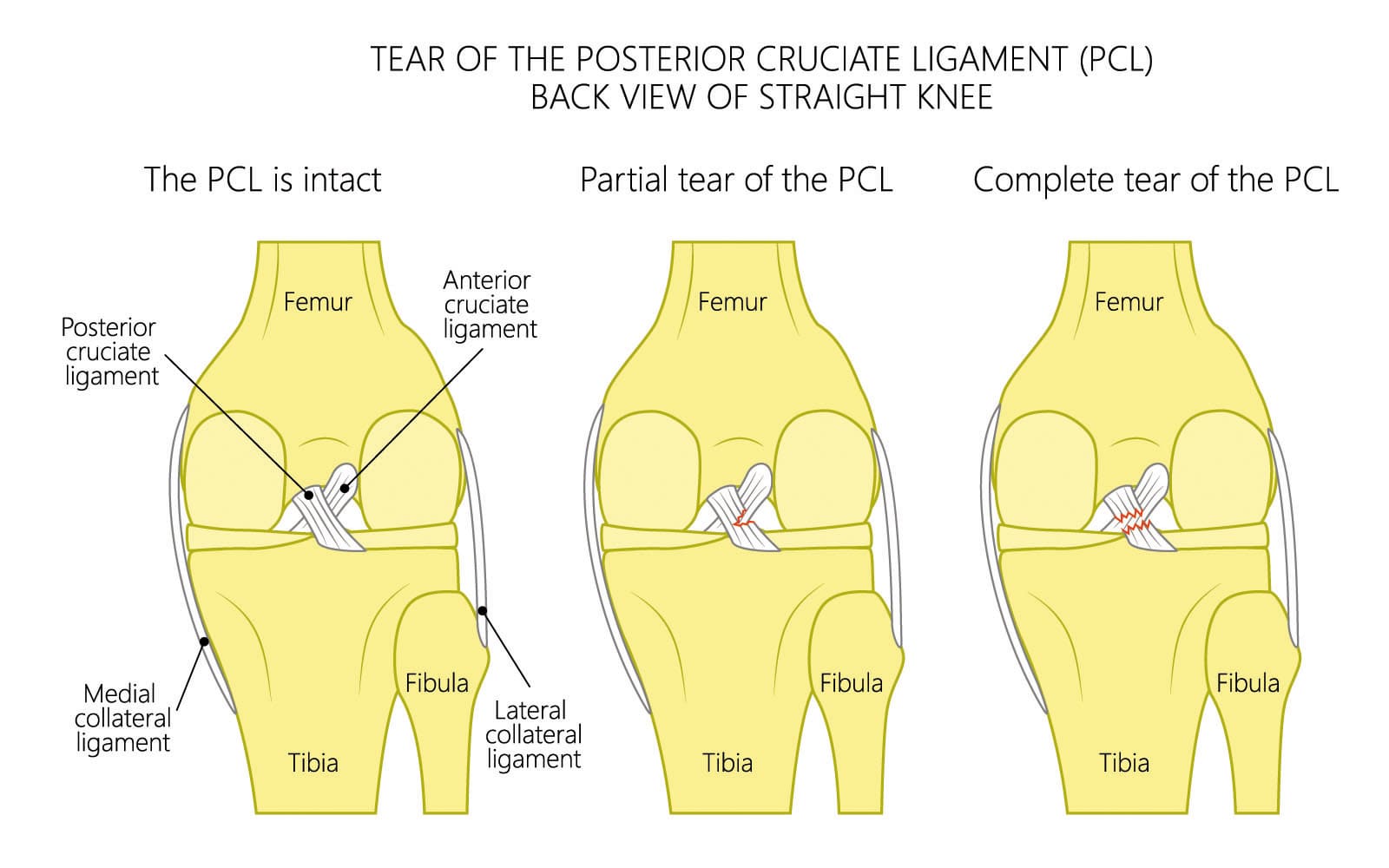

- Other Ligament Injuries: The instability caused by a torn ACL can also put increased stress on other ligaments, such as the medial collateral ligament (MCL) or even the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), leading to further ligamentous damage.

- Long-Term Arthritis: Repeated episodes of instability and secondary damage to the cartilage and menisci significantly increase the risk of developing premature osteoarthritis in the knee. This can lead to chronic pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility.

Why Playing on a Torn ACL is a Bad Idea

Let’s break down the specific reasons why returning to football with a torn ACL is strongly discouraged:

- Loss of Stability: The ACL’s primary role is to prevent the tibia from sliding too far forward under the femur and to limit excessive rotation. Without a functional ACL, this stability is gone.

- Compounding Injuries: As mentioned, the lack of stability makes other knee structures highly vulnerable. Playing through the injury essentially guarantees further damage.

- Increased Pain and Swelling: While some individuals might have a higher pain tolerance, playing will exacerbate inflammation and pain, making recovery more difficult even if no further damage occurs.

- Reduced Performance: Even if one can technically move, the lack of confidence and the knee giving way will drastically impair performance and make one a liability on the field.

- Psychological Impact: The fear of re-injury or the knee giving out can be debilitating, impacting confidence and enjoyment of the sport.

ACL Rupture in Football: Symptoms and Diagnosis

An ACL rupture in football typically presents with a distinct set of symptoms:

- A “Pop” Sensation: Many individuals report hearing or feeling a distinct “pop” at the moment of injury.

- Immediate Pain: Intense pain usually follows the pop.

- Swelling: The knee typically swells rapidly within a few hours of the injury.

- Instability: A feeling of the knee giving way or becoming unstable, especially when trying to change direction or bear weight.

- Limited Range of Motion: Difficulty straightening or bending the knee fully due to pain and swelling.

- Tenderness: Pain upon touching the knee joint line.

Diagnosis usually involves a combination of:

- Physical Examination: A doctor will perform specific tests, such as the Lachman test and the anterior drawer test, to assess the integrity of the ACL.

- Imaging: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for confirming an ACL tear and assessing any associated injuries to the meniscus, cartilage, or other ligaments. X-rays are typically used to rule out fractures.

ACL Surgery Football: The Surgical Path

For athletes who wish to return to high-impact sports like football, ACL reconstruction surgery is often the recommended course of action. This procedure involves replacing the torn ACL with a graft from another part of the body or from a donor.

Types of ACL Grafts

The choice of graft is a crucial decision made in consultation with the orthopedic surgeon. Common graft types include:

- Autografts: These are tissues taken from the patient’s own body.

- Patellar Tendon Graft: This is harvested from the middle third of the patellar tendon (connecting the kneecap to the shinbone). It’s a very strong graft but can sometimes lead to anterior knee pain or difficulty with kneeling.

- Hamstring Tendon Graft: Tendons from the hamstring muscles at the back of the thigh are used. This is a very common and successful option, generally with fewer issues with anterior knee pain.

- Quadriceps Tendon Graft: Tendons from the quadriceps muscle above the kneecap can also be used. This is gaining popularity and offers good strength.

- Allografts: These are grafts taken from a deceased donor. They are useful for older patients or revision surgeries but carry a slightly higher risk of re-tear and may have a slightly slower incorporation into the bone.

The Surgical Procedure

ACL reconstruction surgery is typically performed arthroscopically, meaning it’s done using small incisions and a camera. The surgeon will:

- Prepare the Graft: Harvest the chosen tendon and prepare it for implantation.

- Drill Tunnels: Create tunnels in the femur and tibia where the original ACL was located.

- Pass and Secure the Graft: The graft is then passed through these tunnels and secured with screws or other fixation devices.

ACL Rehabilitation Football: The Long Road Back

Returning to football after ACL surgery is a lengthy and demanding process that requires dedication and strict adherence to a rehabilitation protocol. It’s not just about healing the surgical site; it’s about regaining full strength, flexibility, proprioception (the body’s sense of its position in space), and neuromuscular control.

The entire process, from surgery to a full return to play, can take anywhere from 9 to 12 months, and sometimes longer, depending on the individual’s progress and the surgeon’s guidance.

Phases of ACL Rehabilitation Football

ACL rehabilitation is typically divided into several phases, each with specific goals:

Phase 1: Immediate Post-Operative (Weeks 0-2)

- Goals: Reduce pain and swelling, protect the graft, regain full knee extension, and achieve good quadriceps activation.

- Activities: Pain management (ice, elevation, medication), gentle range of motion exercises (passive and active-assisted), quadriceps sets, straight leg raises, gait training with crutches.

- Key Focus: Preventing stiffness and promoting early healing.

Phase 2: Early Strengthening and Motion (Weeks 2-6)

- Goals: Achieve full passive extension and flexion, build quadriceps and hamstring strength, improve gait, and introduce light weight-bearing.

- Activities: Continue range of motion exercises, stationary cycling, hamstring curls, calf raises, heel slides, light leg press (if pain-free), balance exercises (e.g., single-leg stance).

- Key Focus: Gradually increasing load on the knee while protecting the graft.

Phase 3: Intermediate Strengthening and Neuromuscular Control (Weeks 6-12)

- Goals: Restore normal gait, build endurance, improve balance and proprioception, and begin light functional activities.

- Activities: Introduce closed-chain exercises (squats, lunges), open-chain exercises (leg extensions, but often carefully introduced and monitored), agility drills (e.g., ladder drills, cone drills with slow movements), hamstring curls, calf raises, strengthening of core and hip muscles.

- Key Focus: Re-educating the muscles and improving the knee’s ability to react to movement.

Phase 4: Advanced Strengthening and Sport-Specific Training (Months 3-6)

- Goals: Develop significant strength and power, improve agility and plyometrics, and introduce sport-specific movements.

- Activities: Plyometric exercises (jumping, hopping), agility drills (cutting, pivoting at low speeds), running progression (start with straight-line running, then progress to jogging and controlled changes of direction), sport-specific drills (e.g., passing, dribbling with slow movements).

- Key Focus: Preparing the knee for the demands of football.

Phase 5: Return to Sport Progression (Months 6-12+)

- Goals: Safely return to full football practice and eventually competitive play.

- Activities: Gradual integration into team drills, controlled contact drills, full participation in practice, and finally, clearance for full game participation.

- Key Focus: Ensuring the knee can withstand the forces of football without instability or pain. This phase involves rigorous testing to ensure readiness.

Key Components of ACL Rehabilitation Football

Throughout these phases, several crucial components are emphasized:

- Strength Training: Focusing on quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and calf muscles is vital for supporting the knee.

- Proprioception and Balance: Exercises to retrain the body’s awareness of knee position and improve stability are paramount. This includes exercises on unstable surfaces and single-leg activities.

- Agility and Plyometrics: These exercises gradually reintroduce the cutting, jumping, and landing movements that are integral to football. They are introduced progressively to avoid overloading the healing graft.

- Neuromuscular Control: This refers to the ability of the nervous system and muscles to work together to control the knee joint during movement. This is often impaired after an ACL tear and takes significant retraining.

- Psychological Readiness: Returning to sport involves not just physical readiness but also mental preparedness. Overcoming the fear of re-injury is a significant part of the process.

Returning to Football After ACL: Readiness Criteria

Simply reaching the 9-12 month mark does not automatically mean an athlete is ready to play football. Surgeons and physical therapists use a battery of objective tests to determine readiness. These criteria often include:

- Range of Motion: Full and equal range of motion compared to the uninjured knee.

- Strength: Quadriceps and hamstring strength should be at least 90% of the uninjured leg, measured objectively (e.g., using isokinetic testing).

- Swelling: Minimal to no swelling in the knee.

- Pain: No pain with functional activities.

- Proprioception and Balance: Passing specific balance and proprioception tests.

- Agility and Plyometric Testing: Demonstrating the ability to perform sport-specific movements without pain, instability, or hesitation. This often involves timed hop tests and agility drills.

A study published in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy highlighted that athletes who do not meet specific return-to-sport criteria have a significantly higher risk of re-injury.

Can You Play Football With Torn ACL? The Unvarnished Truth

To reiterate, playing football with a torn ACL is extremely dangerous. The knee is inherently unstable, and the forces involved in football are immense. Attempting to play will likely result in:

- Further Damage: Tearing of the menisci, cartilage damage, and potential injury to other ligaments.

- Chronic Pain and Arthritis: Long-term consequences that can significantly impact quality of life.

- Psychological Trauma: Fear and loss of confidence that can hinder future athletic endeavors.

ACL tears in athletes are common, but the path back requires patience, diligence, and a commitment to proper rehabilitation.

ACL Knee Injury Sports: The Broader Impact

While this discussion focuses on football, ACL knee injury sports are prevalent across many athletic disciplines. Soccer, basketball, skiing, and volleyball also have high rates of ACL tears due to their reliance on cutting, jumping, and pivoting. The principles of diagnosis, surgical management, and rehabilitation are largely consistent across these sports, although specific return-to-sport protocols might be tailored.

The impact of an ACL tear extends beyond the physical. For aspiring athletes, a significant ACL injury can derail collegiate or professional aspirations. The financial costs associated with surgery, rehabilitation, and lost playing time can also be substantial.

ACL Tears in Athletes: Prevention and Considerations

While not all ACL tears can be prevented, several strategies can help reduce the risk:

- Proper Conditioning: Maintaining strong muscles, particularly in the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes, is crucial for knee stability.

- Neuromuscular Training Programs: These programs, often implemented by sports scientists and athletic trainers, focus on improving landing mechanics, balance, and agility to reduce the risk of non-contact ACL injuries.

- Proper Footwear: Wearing appropriate footwear for the playing surface can improve traction and reduce the risk of awkward twists.

- Avoiding Fatigue: Fatigue can impair neuromuscular control, increasing the risk of injury.

- Proper Technique: Athletes should be coached on proper techniques for jumping, landing, and cutting.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: How long does it take to recover from ACL surgery to play football?

A1: Generally, it takes between 9 to 12 months, but sometimes longer, depending on individual healing, rehabilitation progress, and meeting return-to-sport criteria.

Q2: Can I play football with a partial ACL tear?

A2: Even a partial tear can lead to instability and further damage. While some may attempt to play, it’s highly discouraged as it significantly increases the risk of a complete tear and secondary injuries.

Q3: What is the success rate of ACL reconstruction surgery?

A3: The success rate for ACL reconstruction surgery is generally high, with most patients able to return to their pre-injury activity levels. However, re-tear rates exist, particularly in younger, high-risk athletes.

Q4: Will my knee feel the same after ACL surgery?

A4: While the goal is to restore function, some individuals may notice subtle differences in sensation or may experience some residual stiffness or weakness. Meticulous rehabilitation helps minimize these effects.

Q5: Is playing football with a torn ACL worth the risk?

A5: No. The potential for long-term damage, chronic pain, and career-ending complications far outweighs any perceived short-term benefit. Prioritizing proper healing and rehabilitation is essential.

Conclusion

The allure of playing football is strong, but for individuals with a torn ACL, the field is a dangerous place. Attempting to play with a torn ACL risks further debilitating injuries, long-term knee problems like arthritis, and can even jeopardize future athletic participation. The journey back to football after an ACL tear is a marathon, not a sprint, demanding commitment to a structured rehabilitation program. By embracing the recovery process and meeting objective return-to-sport criteria, athletes can significantly improve their chances of a safe and successful return to the game they love, with a stable and healthy knee.